In the Tibetan Buddhist tradition the achievement of shamatha is said to be indispensable for those wanting to realise Buddhahood.

Yet it is often overlooked or the teachings are watered down heavily.

Shamatha is known as access to the first dhyana (jhana). It marks the threshold between our desire realm and the more refined form realm.

Today in the modern world you often get weekend dhyana workshops. Many on the Internet claim that they’ve achieved the first, second, third and even fourth dhyana.

Unfortunately I think a lot of those claims are exaggerated, or they use a watered down benchmark for what it actually means to achieve shamatha and beyond into the dhyanas..

In this essay I look at what shamatha is and what it means to fully achieve it. I touch on the requirements needed to achieve it and why one would dedicate so much time towards it. I then look at the role of deliberate practice and how shamatha practitioners can learn a lot from elite athletes, musicians and craftsman.

What is Shamatha?

I quote from my teacher B. Alan Wallace a lot below, mainly from The Attention Revolution.

Shamatha is a Sanskrit word which has two primary meanings. Shamatha is firstly “an array of methods that are designed to develop your attention and meta cognitive skills.” There are three primary shamatha methods that Alan Wallace teaches:

- Mindfulness of Breathing

- Settling the Mind in its Natural State

- Awareness of Awareness

Each of these methods have several variations. There are also many other methods taught by the Buddha, some involve using a kasina, a mental image or even a stick, stone or candle that you look at. They can all be classified as shamatha methods. Each method can also take one all the way to the achievement of shamatha, which is the second meaning of the word.

In Tibetan Buddhist it is widely regarded that the achievement of shamatha is indispensable on the path towards Buddhahood. However shamatha on it’s own is non-sectarian. It is not unique to Buddhism, and can be found by different names in other contemplative traditions. “It entails no belief system. No commitment to any ideology or any institution or any group.” It can therefore be seen as contemplative technology. What one decides to apply their shamatha to is up to them.

Upon the achievement of shamatha, Alan Wallace writes that you can focus effortlessly and unwaveringly upon your chosen object for at least four hours.

I remember the first time I heard about meditation. I read a WikiHow article giving instructions on how to meditate. It instructed to set a timer for five minutes, then direct my attention to the sensations of my breath in my body. I thought, “OK, that sounds easy.”

Five minutes later I realised how insane I actually was. It was such a simple task, yet I couldn’t do it. My mind was racing and chattering so much. I would be able to stay on the breath for maybe 4 or 5 seconds before I got distracted by a thought or some noise.

It’s difficult to sit quietly and keep my attention still. I would guess this is the same for you. It points to a deep truth highlighted by Blaise Pascal in this quote:

“All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

I admire anyone who can sit still for four hours. Yet with the achievement of shamatha, it is not just about sitting still for 4 hours. It’s sitting while having one’s mental attention remain unwavering on the meditation object (e.g. the breath, a mental image or awareness itself.)

Try this simple experiment. Take any object, like a pen. Direct your eyes towards the pen and let your physical gaze rest there for a few seconds.

Now direct your mental attention to the pen, and let it rest there too.

Any time your mental attention is pulled away from the pen, you are no longer maintaining unwavering attention.

The Transformative Effects of Achieving Shamatha

As well as the four hour benchmark, at a week-long shamatha retreat I attended in 2016, we were given a list of all the effects said to happen when one achieves shamatha. I include only a partial list below, but you can see the full list here.

Effects during meditation:

- Any thoughts that arise naturally subside, without proliferating.

- There is no sensory awareness of your body or environment.

- You have a sense as if your mind has become indivisible with space.

- You experience a mental bliss to such a degree that you do not wish to arise from meditation.

Effects that linger outside of meditation:

- Your attention is highly focused throughout all daily activities.

- You experience an unprecedented fitness of body and mind, such that you are naturally inclined towards virtue.

- For the most part, the five obscurations—(1) sensual craving, (2) malice, (3) laxity and dullness, (4) excitation and anxiety, and (5) afflictive uncertainty—do not arise.

- Due to bodily fitness, there is no feeling of physical heaviness or discomfort, the spine becomes straight like a golden pillar, and the body feels blissful as if it were bathed with warm milk.

- Due to mental fitness, you are now fully in control of your mind, so you are virtually free of sadness and grief and continuously experience a state of well-being (however you can still be empathetic to the sadness and grief of others).

These effects are nothing to be scoffed at. This is exceptional mental health. When I read that list of effects and compare it to my current mental state, I understand better why when referring to not having achieved shamatha, the Buddha said:

So long as these five obscurations are not abandoned one considers oneself as indebted, sick, in bonds, enslaved and lost in a desert track.

Put simply, shamatha is a way of refining the mind in a specific way that makes the mind serviceable, flexible, malleable and useful for all kinds of activities. In Buddhism, the core activity is to realise Buddhahood.

The Gold Standard

From my superficial research into this topic, the only person I have come across who offers the highest benchmark for the achievement of shamatha is Alan Wallace. It isn’t his own made up benchmark. Rather he cites sources like Buddhaghosa, Asanga, Atisha and Padmasambhava. All very authoritative sources within Tibetan Buddhism.

What I go by is simply that it’s the highest benchmark I’ve seen. That by itself doesn’t mean it’s correct. But the purpose of shamatha, at least within Buddhism, is to realise Buddha mind. If one’s shamatha is subpar, there are big traps to fall into by thinking one has greater realisations than they have. It’s not just ignorance, but delusion. Believing you have arrived somewhere when you haven’t. Meaning there is no more searching. One is stuck.

A few things that stood out for me when I read The Attention Revolution and the description of shamatha.

- After achieving shamatha, when you meditate, all your physical senses implode. There is no signal.

This means you could be by the side of a road, enter shamatha, and not hear a single car.

There are levels to this. The deeper into dhyana one goes (from the first to the fourth), the harder it becomes for the physical senses to disrupt the dhyana. It’s similar in parts to being asleep. During different parts of the night you will be more deeply asleep, meaning it is harder to wake you. Other times your sleep is shallow and a soft sound might wake you.

- You can sit for at least four hours.

Meaning sitting much longer than that is easy. Six, eight, ten hours would be no problem. This is without moving. Without any signal from your physical senses coming in for that entire duration.

- Some siddhis might become available to you.

Siddhis is the sanskrit word for supernatural powers. Things like clairvoyance, precognition and past life recall.

This of course is not the purpose of shamatha. But for some people siddhis can pop up quite spontaneously after achieving shamatha.

- You can get bliss, luminosity and non-conceptuality on tap

Whenever you want, you can access bliss. And you can sustain it for hours and hours, without it getting boring. Likewise for luminosity (as in high intensity, a sheer vividness) and non-conceptuality (a peacefulness, serenity).

- When you achieve shamatha, it’s very unlikely you will lose it in this lifetime.

Alan Wallace was quoting HH Dalai Lama on this. He said that unless you get into a car accident with very serious head injuries, it is very unlikely that you will lose shamatha once you’ve achieved it. He then continued that you might lose it when you go through the bardo (the intermediate state between lives) but that it would be much easier to re-achieve shamatha in the next life.

What I read about shamatha makes me very doubtful about people achieving deep states of dhyana after a weekend workshop. Perhaps it’s very possible to have genuine glimpses of deeper states – but the mastery and long-term benefits from shamatha require sustained deliberate practice.

Modern Science on Shamatha and Beyond

Modern science knows a lot about negative states of mind, as seen in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Yet when it comes to exceptional mental states of well-being, modern science is lacking. But recent studies on “Olympic-level” contemplatives, with 10,000 to 60,000 hours of meditation practice have shown that the potential of human flourishing is vast. It shows that the above effects of shamatha and beyond are very possible.

Here are some quotes from Altered Traits, a book by Richard Davidson and Dan Goleman on the latest meditation research:

… yogis like Mingyur seem to experience an ongoing state of open, rich awareness during their daily lives, not just when they meditate.

This effect also seems to persist at night, where the “brain-entraining gamme pattern goes on even while seasoned meditators are asleep.” The yogis studied were also capable of displaying extraordinary degrees of control over their own minds:Like Mingyur, they entered the specified meditative states at will, each one marked by a distinctive neural signature. As with Mingyur these adepts have shown remarkable mental dexterity, with striking ease instantly mobilizing these states: generating feelings of compassion; the spacious equanimity of complete openness to whatever occurs; or a laser-tight, unbreakable focus.

And when compared to “normal” people:

Mingyur’s brain’s circuitry for empathy (which typically fires a bit during this mental exercise) rose to an activity level 700 to 800 times greater than it had been during the rest period just before.

Such an extreme increase befuddles science; the intensity with which those states were activated in Mingyur’s brain exceeds any we have seen in studies of “normal” people. The closest resemblance is for epileptic seizures, but those episodes last brief seconds, not a full minute.

With individuals like Mingyur, modern science is being stretched for what is possible for the human mind. It also means that it’s clear something akin to shamatha is possible to achieve.

How to Achieve Shamatha

Atisha writes that there are six core requirements to achieve shamatha:

- Pure ethical discipline

- Few desires

- Contentment with what one has

- Limiting one’s activities

- A harmonious and quiet environment where food and shelter is easily obtained

- Being free from rumination and compulsive thinking

He also writes that if the conditions for shamatha are not met, one can meditate for a thousand years and never achieve it.

In Tibetan oral tradition, it is said that those of sharpest faculties may achieve shamatha in three months. Those of medium, in six months and those of dull faculties in nine months.

So take out several months to spend in full-time retreat. Read the instructions for how to meditate in The Attention Revolution, or work through one of the shamatha podcasts. Set a daily schedule and practice practice practice.

Alan recommends starting with multiple short (15 minute) sessions. Quality is important. As you get better, increase the length by a minute or two. Continue like this until you’ve achieved shamatha and are sitting one or two sessions per day of multiple hours each. E.g. An 11 hour sit and a 5 hour sit.

Not easy!

But possible.

In my own life, I have tried to create the conditions for me to be able to achieve shamatha. I have done several retreats now. They range from two weeks to six months. But I have not achieved shamatha. I am definitely of the very, very dull faculties segment of practitioners.

While I think my external conditions have been good enough, I have not given it enough time. But with longer time, I need stronger inner conditions. And that is still lacking. It’s why instead of deciding to go into another longer retreat, I am back in London and have a set up where I still have lots of free time for practice, but also to write.

Writing brings me greater clarity and it is a good process to help me reach deeper into my motivation for practice. It’s a core reason for writing this essay now.

Alan writes:

This level of professional training may seem daunting and unfeasible to most readers… but compare it to the training of Olympic athletes. Only a small number of individuals have the time, ability, and inclination to devote themselves to such training, which can appear at first glance to have little relevance for the diverse practical problems facing humanity today. But research on serious athletes has yielded many valuable insights concerning diet, exercise, and human motivation that are relevant to the general public. While the training of Olympic athletes is focused primarily on achieving physical excellence, this attentional training is concerned with achieving optimal levels of attentional performance.

The Attention Revolution

It’s something I am having to come to grips with through my writing. Am I willing to dedicate my entire life to this endeavour? Where my peers might be progressing in their careers, settling down with their spouse and starting families, I’ll be alone in a cabin meditating. Is this something I genuinely want to do with my life?

Having already started an attempt to achieve shamatha, the biggest challenge I feel is tapping into the why. The how is relatively straight forward. It’s simple, but definitely not easy.

Why Achieve Shamatha?

I answer this question in more depth in another essay titled The True Extent of Suffering. The gist is that suffering doesn’t terminate at death. It continues. There is no natural end or beginning in sight. Death is a continuation of a cycle.

When birth comes again, amnesia is prevalent. And thus each new life is filled with forgetfulness. The primary role of shamatha is non-forgetfulness. It’s why it’s so crucial in breaking this cycle of birth and death. As I said above, shamatha is considered indispensable for the realisation of Buddhahood. To ask why achieve shamatha is nearly the same as asking why realise Buddhahood.

Yet as mainstream science continues researching meditation and it’s benefits – there may be more and more people willing and able to achieve shamatha without the motivation of wanting to realise Buddhahood too.

Shamatha is after all non-sectarian. And it is written about not just in Buddhism but in many other contemplative traditions under different names. As with any craft, there are also natural intrinsic rewards that make the practice meaningful in and of itself. The bliss, serenity and joy that come from shamatha practice can be very self-motivating.

But in a culture where we do not (yet) have professional meditators, taking extended time out for practice can prove very difficult. Professional athletes often can receive scholarships. In many sports there are professional leagues to aspire to. Would the number of meditators fully achieving shamatha skyrocket if there were greater economic support for it?

Nine Stages to Shamatha

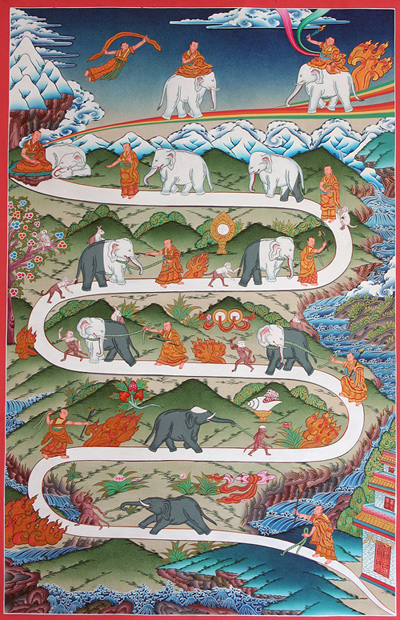

One very popular diagram in Buddhism is the nine stages to shamatha. It shows a monk taming a wild elephant, which symbolises the mind. There is also a monkey, representing distractions (excitation), and a rabbit, representing dullness or laxity.

The nine stages are as follows:

- Directed attention

- Continuous attention

- Resurgent attention

- Close attention

- Tamed attention

- Pacified attention

- Fully pacified attention

- Single-pointed attention

- Attentional balance

- Shamatha

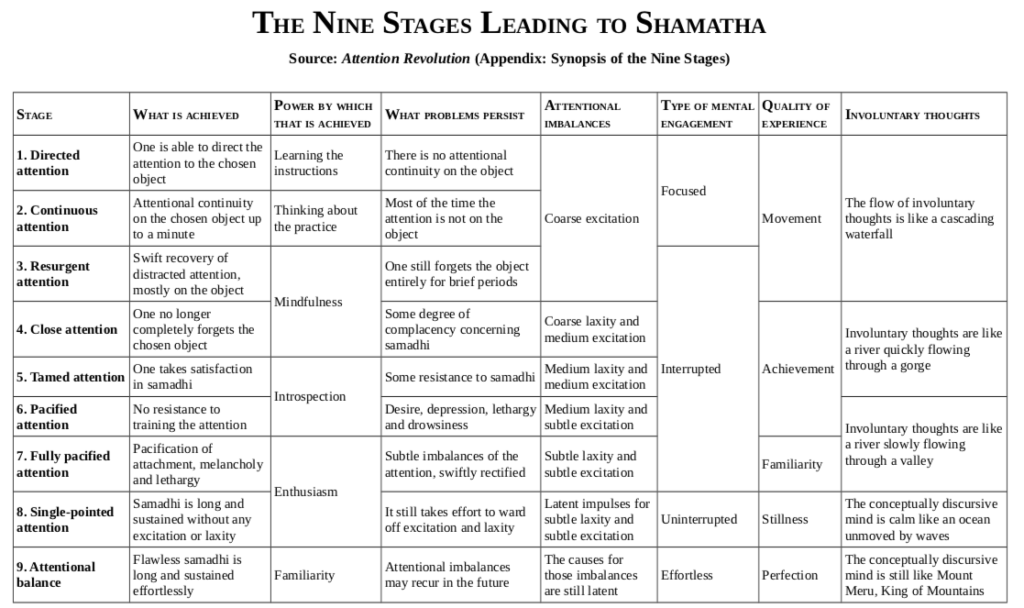

In the Attention Revolution there is a great diagram showing the key characteristics for each of the nine stages.

The Role of Deliberate Practice

In Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Outliers, he suggests that “the key to achieving world-class expertise in any skill, is, to a large extent, a matter of practicing the correct way, for a total of around 10,000 hours.” I think for shamatha, at least 10,000 hours sounds about right.

However, numbers can be deceptive. It’s a bit too prescriptive and in digging further the 10,000 hour figure seems to have been chosen arbitrarily anyway:

… there is nothing special or magical about 10,000 hours. Gladwell could just as easily have mentioned the average amount of time the best violin students had practiced by the time they were eighteen (approximately 7400 hours) but he chose to refer to the total practice time they had accumulated by the time they were twenty, because it was a nice round number.

The 10,000 hour figure also doesn’t take into account the quality of practice. And this is something Alan does stress. There is no point forcing yourself to sit for hours and hours if the quality of mindfulness and introspection is zero. Anders Ericsson shares here about deliberate practice:

Third, Gladwell didn’t distinguish between the type of practice that the musicians in our study did–a very specific sort of practice referred to as “deliberate practice” which involves constantly pushing oneself beyond one’s comfort zone, following training activities designed by an expert to develop specific abilities, and using feedback to identify weaknesses and work on them–and any sort of activity that might be labeled “practice.”

This passage reminds me of something I’ve posted about from meditation teacher Shinzen Young. He describes three accelerators to practice – which are designed with deliberate practice in mind.

1) Trigger Practices

You expose yourself to a sight, sound, or physical-type body sensation that would tend to create a mental and/or emotional reaction within you. The stimulus could create a certain type of pleasant reactions (love, joy, interest…) or a certain type of unpleasant reaction (anger, fear, sadness, shame…). You vary the type, intensity, duration, and spacing of the stimulation so that you’re working against an edge but not overloading yourself (as in weight training).

The typical example I give is a friend I know who has spent hundreds of hours in McDonald’s meditating.

2) Duration Training

Refers to learning how to maintain “practice in stillness” for longer and longer periods of time. Practice in stillness means formal sessions where you don’t move much or at all. One traditional form of Duration Training is known as adhiṭṭhāna (strong determination sitting or “breaking through a posture”). In adhiṭṭhāna, you decide to sit for a period of time (1 hour, 2 hours, 3 hours, 4 hours, a day, a week…) with little or no voluntary movement.

3) Challenge Sequence

Take any meditation technique you relate to and attempt to maintain it through a sequence of progressively more challenging movements and activities. Stay with each stage for however long it takes you to get as deep as you were in the previous stage. E.g. standing, slow walking, faster walking, walking in a sensorily impactful environment.

The key to engaging in these deliberate practices for shamatha is to maintain the foundation of relaxation throughout. Alan warns again and again about the dangers of striving too much in shamatha practice. In effect, the whole practice is to relax more and more and more. So discussions on deliberate practice need to have this caveat.

Excitation and Laxity

The two biggest challenges in shamatha practice are excitation and laxity. They keep coming back again and again in subtler ways until the achievement of shamatha. Both can be broken down into three gradations: coarse, medium and subtle.

Coarse excitation is when your attention is on the object (let’s say a rock) and because of a distraction, 100% of your attention moves away from the rock.

Medium excitation is when only about half of your attention moves away from the rock. If you were gazing at the rock, it would be like your gaze looking elsewhere but your periphery still being aware of the rock.

Subtle excitation is where your gaze is primarily on the rock, but peripherally you notice excitations.

For coarse laxity it is like a cloud of dullness obscures the object, so that even though you might be looking directly at it – you cannot see the object anymore.

Medium laxity is when you can still see aspects of the object, even though there is laxity present.

Subtle laxity is when the object is seen, but it’s not quite as sharp as you’ve experienced it before.

It’s important to note that these indicators are all subjective. There is no objective measure here. How you discern what is coarse, medium or subtle depends on previous subjective benchmarks.

For example on a given session you might reflect back on it and think, “Wow that was the most clear and vivid meditation session I’ve ever experienced.” You can then make a mental note of that session and when you notice that your current session isn’t as sharp as that one, you know some form of laxity is present.

The deeper you go, the subtler you get in discernment. What you used to call subtle laxity might now be called coarse laxity.

A Source of Genuine Happiness

For something to be a source of something it needs to fulfill two things:

- Every time you go there, you get it.

- The longer you stay there, the more of it you get.

For example, an artisian well is a genuine source of water. Every time you go there, you get water. The longer you stay there, the more water you get. If you go there on a Sunday and you get water, but on a Wednesday you don’t get water, it’s not a source of water.

When it comes to happiness, I feel very few have found genuine sources.

Whenever I eat dark chocolate, I get some amount of happiness. But it’s not true that the more dark chocolate I eat, the more happiness I get. At some point I get sick of it. This is likewise for sex, video games, and even spending time with loved ones.

But with shamatha practices, there is something very interesting that seems to happen. There seems to be a source of happiness here. For me, when practicing the shamatha method of Awareness of Awareness, I notice it most clearly. Every time I go there, I experience a degree of joyfulness. Sometimes bliss, and sometimes just pure intensity.

These qualities increase the longer I stay resting in awareness. As far as I can tell, they continue seemingly indefinitely – what seems to happen is I get kicked out rather than the source dries up. As in I lose my ability to maintain mindfulness on the object (awareness).

The implications of this are astounding for an individual’s life. All of us yearn for happiness. We yearn to be free of suffering. What sort of transformation happens to an individual when he or she has found a true source of happiness?

A source of happiness that requires no money to buy. No fancy car. No mansion or perfect partner. No external conditions whatsoever.

It just springs up, whenever you want it. On demand, for as long as you want.

And it doesn’t get boring.

Society might become incredibly unproductive.

A Year of Silence: Shamatha Gap Year Program

What if just like how popular it is among young people to take a gap year – volunteering in a different country or travelling – spending a few months or a full year practicing shamatha became as popular?

What kind of generation would that create?

As a practicing Buddhist, I personally want to explore the validity of the Buddhist worldview – samsara and the whole lot. Yet I know most people are not Buddhists. And I know the non-sectarian practices of shamatha have incredible value.

So in this section I’m asking, what cultural shifts are needed for something like a “Year in Silence” gap year program to become popular among 18-year olds?

I don’t have the answers for now. But it feels like a meaningful question to hold.

Human beings can’t bear silence. It would mean that they would bear themselves.

Pascal Mercier

Conclusion

The practices of shamatha within Buddhism are not unique to Buddhism. They go by different names in other traditions, but the practice is the same.

Shamatha is exceptional mental balance. It’s discovering a genuine source of happiness. Albeit not ultimate – but at a non-sectarian level this is a far superior source than anything mainstream culture shares.

The achievement of shamatha isn’t a trivial one. It requires an Olympic athlete type commitment. Most people are not able to put in such time and energy. Yet the practices of shamatha can be done by anyone, and can benefit anyone, regardless if one has achieved shamatha fully or not.

I envision a world where dedicated shamatha practices become a normal part of society, especially among the youth. Where the role of deliberate practice and deep work is encouraged so that one can deepen self-awareness, attention skills and find true sources of happiness.

Thank you!

I am truly impressed by your ability to write with such eloquence in a totally contemporaneous and engaging way.

You summarise profound texts and ideas with ease, and make them graspable.

I spoke with you today at the end of Alan’s retreat in Wales, on The Seven Point Mind Training despite having sat just slightly behind you and to your left throughout the entire silent retreat……

Once I arrived home, I got browsing on the Cultivating Emotional Balance website and then a link to teachers in the UK I saw your name….and recognised it as the person with whom I spoke briefly just as we were dispersing after breakfast and going our own ways.

How thankful I am for having met you.

Dear Marisol, thanks for writing this comment – and finding this article ha. Still got lots to work on here. It keeps getting bigger the more I come back to it!

Hope your moving to London goes well. And again the Awakin circles in London are a good place to get plugged into London :-).

Really interesting. Skimmed, but bookmarked to come back to and read thoroughly. Would you say Shamatha is similar to savikalpa samadhi in the yoga sutras? Both of these states seem to be where one is no longer conscious of the outer world. The body enters a trance where awareness is immersed in inner oneness. If so, this wouldn’t be the end goal you’d hope to achieve, right? It’d be nirvana (or nirvikalpa samadhi) where there’s a union between external and internal that you can enter in and out of at will. In Shamatha the body is transfixed, so the state, while blissful, would be fleeting. Anyway, really cool blog. Keep it up 🙂

Hey Bryce, thanks for the comment! Still a work in progress this post so would love to hear your feedback if you do come back to reading it :-).

I’m not very familiar with savikalpa samadhi but from your brief description yes they do seem similar. Shamatha is also called access to the first dhyana, which is access to form realm. It is said humans are in the desire realm and upon achieving shamatha (or beyond into the first dhyana, second, third etc) then one goes deeper into the form realms and there is no longer awareness of the desire realm.

But yes it’s certainly not the end goal at all. Just an important tool in order to move towards the end goal. From the teachings I’ve received shamatha has to be unified with vipashyana in order to gain insights that are irreversible.

Liam,

I think you should look at Christianity also, not just Buddhism.

Thank you

Thanks for your comment Anthony. I’d love to explore Christianity more. Any particular reason why in regards to this blogpost?

Liam, I remember in your post of how your family went to church. I am wondering if you are still practicing Christianity.

Thank you

Hi Anthony,

Not actively no. I practice Buddhism.